@ -0,0 +1,109 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Introduction au machine learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://youtu.be/lTd9RSxS9ZE "ML, AI, deep learning - What's the difference?")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> 🎥 Cliquer sur l'image ci-dessus afin de regarder une vidéo expliquant la différence entre machine learning, AI et deep learning.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz préalable](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/1?loc=fr)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Introduction

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Bienvenue à ce cours sur le machine learning classique pour débutant ! Que vous soyez complètement nouveau sur ce sujet ou que vous soyez un professionnel du ML expérimenté cherchant à peaufiner vos connaissances, nous sommes heureux de vous avoir avec nous ! Nous voulons créer un tremplin chaleureux pour vos études en ML et serions ravis d'évaluer, de répondre et d'apprendre de vos retours d'[expériences](https://github.com/microsoft/ML-For-Beginners/discussions).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://youtu.be/h0e2HAPTGF4 "Introduction to ML")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> 🎥 Cliquer sur l'image ci-dessus afin de regarder une vidéo: John Guttag du MIT introduit le machine learning

|

||||||

|

### Débuter avec le machine learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Avant de commencer avec ce cours, vous aurez besoin d'un ordinateur configuré et prêt à faire tourner des notebooks (jupyter) localement.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Configurer votre ordinateur avec ces vidéos**. Apprendre comment configurer votre ordinateur avec cette [série de vidéos](https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlrxD0HtieHhS8VzuMCfQD4uJ9yne1mE6).

|

||||||

|

- **Apprendre Python**. Il est aussi recommandé d'avoir une connaissance basique de [Python](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/python-language/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa), un langage de programmaton utile pour les data scientist que nous utilisons tout au long de ce cours.

|

||||||

|

- **Apprendre Node.js et Javascript**. Nous utilisons aussi Javascript par moment dans ce cours afin de construire des applications WEB, vous aurez donc besoin de [node](https://nodejs.org) et [npm](https://www.npmjs.com/) installé, ainsi que de [Visual Studio Code](https://code.visualstudio.com/) pour développer en Python et Javascript.

|

||||||

|

- **Créer un compte GitHub**. Comme vous nous avez trouvé sur [GitHub](https://github.com), vous y avez sûrement un compte, mais si non, créez en un et répliquez ce cours afin de l'utiliser à votre grés. (N'oublier pas de nous donner une étoile aussi 😊)

|

||||||

|

- **Explorer Scikit-learn**. Familiariser vous avec [Scikit-learn](https://scikit-learn.org/stable/user_guide.html), un ensemble de librairies ML que nous mentionnons dans nos leçons.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Qu'est-ce que le machine learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Le terme `machine learning` est un des mots les plus populaire et le plus utilisé ces derniers temps. Il y a une probabilité accrue que vous l'ayez entendu au moins une fois si vous avez une appétence pour la technologie indépendamment du domaine dans lequel vous travaillez. Le fonctionnement du machine learning, cependant, reste un mystère pour la plupart des personnes. Pour un débutant en machine learning, le sujet peut nous submerger. Ainsi, il est important de comprendre ce qu'est le machine learning et de l'apprendre petit à petit au travers d'exemples pratiques.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Google Trends montre la récente 'courbe de popularité' pour le mot 'machine learning'

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Nous vivons dans un univers rempli de mystères fascinants. De grands scientifiques comme Stephen Hawking, Albert Einstein et pleins d'autres ont dévoués leur vie à la recherche d'informations utiles afin de dévoiler les mystères qui nous entourent. C'est la condition humaine pour apprendre : un enfant apprend de nouvelles choses et découvre la structure du monde année après année jusqu'à qu'ils deviennent adultes.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Le cerveau d'un enfant et ses sens perçoivent l'environnement qui les entourent et apprennent graduellement des schémas non observés de la vie qui vont l'aider à fabriquer des règles logiques afin d'identifier les schémas appris. Le processus d'apprentissage du cerveau humain est ce que rend les hommes comme la créature la plus sophistiquée du monde vivant. Apprendre continuellement par la découverte de schémas non observés et ensuite innover sur ces schémas nous permet de nous améliorer tout au long de notre vie. Cette capacité d'apprendre et d'évoluer est liée au concept de [plasticité neuronale](https://www.simplypsychology.org/brain-plasticity.html), nous pouvons tirer quelques motivations similaires entre le processus d'apprentissage du cerveau humain et le concept de machine learning.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Le [cerveau humain](https://www.livescience.com/29365-human-brain.html) perçoit des choses du monde réel, assimile les informations perçues, fait des décisions rationnelles et entreprend certaines actions selon le contexte. C'est ce que l'on appelle se comporter intelligemment. Lorsque nous programmons une reproduction du processus de ce comportement à une machine, c'est ce que l'on appelle intelligence artificielle (IA).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Bien que le terme peut être confu, machine learning (ML) est un important sous-ensemble de l'intelligence artificielle. **ML se réfère à l'utilisation d'algorithmes spécialisés afin de découvrir des informations utiles et de trouver des schémas non observés depuis des données perçues pour corroborer un processus de décision rationnel**.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Un diagramme montrant les relations entre AI, ML, deep learning et data science. Infographie par [Jen Looper](https://twitter.com/jenlooper) et inspiré par [ce graphique](https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/366996/distinction-between-ai-ml-neural-networks-deep-learning-and-data-mining)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Ce que vous allez apprendre dans ce cours

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dans ce cours, nous allons nous concentrer sur les concepts clés du machine learning qu'un débutant se doit de connaître. Nous parlerons de ce que l'on appelle le 'machine learning classique' en utilisant principalement Scikit-learn, une excellente librairie que beaucoup d'étudiants utilisent afin d'apprendre les bases. Afin de comprendre les concepts plus larges de l'intelligence artificielle ou du deep learning, une profonde connaissance en machine learning est indispensable, et c'est ce que nous aimerions fournir ici.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dans ce cours, vous allez apprendre :

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Les concepts clés du machine learning

|

||||||

|

- L'histoire du ML

|

||||||

|

- ML et équité (fairness)

|

||||||

|

- Les techniques de régression ML

|

||||||

|

- Les techniques de classification ML

|

||||||

|

- Les techniques de regroupement (clustering) ML

|

||||||

|

- Les techniques du traitement automatique des langues (NLP) ML

|

||||||

|

- Les techniques de prédictions à partir de séries chronologiques ML

|

||||||

|

- Apprentissage renforcé

|

||||||

|

- D'applications réels du ML

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Ce que nous ne couvrirons pas

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Deep learning

|

||||||

|

- Neural networks

|

||||||

|

- IA

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Afin d'avoir la meilleur expérience d'apprentissage, nous éviterons les complexités des réseaux neuronaux, du 'deep learning' (construire un modèle utilisant plusieurs couches de réseaux neuronaux) et IA, dont nous parlerons dans un cours différent. Nous offirons aussi un cours à venir sur la data science pour concentrer sur cet aspect de champs très large.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Pourquoi etudier le machine learning ?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Le machine learning, depuis une perspective systémique, est défini comme la création de systèmes automatiques pouvant apprendre des schémas non observés depuis des données afin d'aider à prendre des décisions intelligentes.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Ce but est faiblement inspiré de la manière dont le cerveau humain apprend certaines choses depuis les données qu'il perçoit du monde extérieur.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ Penser une minute aux raisons qu'une entreprise aurait d'essayer d'utiliser des stratégies de machine learning au lieu de créer des règles codés en dur.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Les applications du machine learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Les applications du machine learning sont maintenant pratiquement partout, et sont aussi omniprésentes que les données qui circulent autour de notre société (générés par nos smartphones, appareils connectés ou autres systèmes). En prenant en considération l'immense potentiel des algorithmes dernier cri de machine learning, les chercheurs ont pu exploités leurs capacités afin de résoudre des problèmes multidimensionnels et interdisciplinaires de la vie avec d'important retours positifs

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Vous pouvez utiliser le machine learning de plusieurs manières** :

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Afin de prédire la possibilité d'avoir une maladie à partir des données médicales d'un patient.

|

||||||

|

- Pour tirer parti des données météorologiques afin de prédire les événements météorologiques.

|

||||||

|

- Afin de comprendre le sentiment d'un texte.

|

||||||

|

- Afin de détecter les fake news pour stopper la propagation de la propagande.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

La finance, l'économie, les sciences de la terre, l'exploration spatiale, le génie biomédical, les sciences cognitives et même les domaines des sciences humaines ont adapté le machine learning pour résoudre les problèmes ardus et lourds de traitement des données dans leur domaine respectif.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Le machine learning automatise le processus de découverte de modèles en trouvant des informations significatives à partir de données réelles ou générées. Il s'est avéré très utile dans les applications commerciales, de santé et financières, entre autres.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dans un avenir proche, comprendre les bases du machine learning sera indispensable pour les personnes de tous les domaines en raison de son adoption généralisée.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

## 🚀 Challenge

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Esquisser, sur papier ou à l'aide d'une application en ligne comme [Excalidraw](https://excalidraw.com/), votre compréhension des différences entre l'IA, le ML, le deep learning et la data science. Ajouter quelques idées de problèmes que chacune de ces techniques est bonne à résoudre.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz de validation des connaissances](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/2?loc=fr)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Révision et auto-apprentissage

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Pour en savoir plus sur la façon dont vous pouvez utiliser les algorithmes de ML dans le cloud, suivez ce [Parcours d'apprentissage](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/create-no-code-predictive-models-azure-machine-learning/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Devoir

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Être opérationnel](assignment.fr.md)

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,107 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Pengantar Machine Learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://youtu.be/lTd9RSxS9ZE "ML, AI, deep learning - Apa perbedaannya?")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> 🎥 Klik gambar diatas untuk menonton video yang mendiskusikan perbedaan antara Machine Learning, AI, dan Deep Learning.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz Pra-Pelajaran](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/1/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Pengantar

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Selamat datang di pelajaran Machine Learning klasik untuk pemula! Baik kamu yang masih benar-benar baru, atau seorang praktisi ML berpengalaman yang ingin meningkatkan kemampuan kamu, kami senang kamu ikut bersama kami! Kami ingin membuat sebuah titik mulai yang ramah untuk pembelajaran ML kamu dan akan sangat senang untuk mengevaluasi, merespon, dan memasukkan [umpan balik](https://github.com/microsoft/ML-For-Beginners/discussions) kamu.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://youtu.be/h0e2HAPTGF4 "Pengantar Machine Learning")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> 🎥 Klik gambar diatas untuk menonton video: John Guttag dari MIT yang memberikan pengantar Machine Learning.

|

||||||

|

### Memulai Machine Learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sebelum memulai kurikulum ini, kamu perlu memastikan komputer kamu sudah dipersiapkan untuk menjalankan *notebook* secara lokal.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Konfigurasi komputer kamu dengan video ini**. Pelajari bagaimana menyiapkan komputer kamu dalam [video-video](https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlrxD0HtieHhS8VzuMCfQD4uJ9yne1mE6) ini.

|

||||||

|

- **Belajar Python**. Disarankan juga untuk memiliki pemahaman dasar dari [Python](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/python-language/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa), sebuah bahasa pemrograman yang digunakan oleh data scientist yang juga akan kita gunakan dalam pelajaran ini.

|

||||||

|

- **Belajar Node.js dan JavaScript**. Kita juga menggunakan JavaScript beberapa kali dalam pelajaran ini ketika membangun aplikasi web, jadi kamu perlu menginstal [node](https://nodejs.org) dan [npm](https://www.npmjs.com/), serta [Visual Studio Code](https://code.visualstudio.com/) yang tersedia untuk pengembangan Python dan JavaScript.

|

||||||

|

- **Buat akun GitHub**. Karena kamu menemukan kami di [GitHub](https://github.com), kamu mungkin sudah punya akun, tapi jika belum, silakan buat akun baru kemudian *fork* kurikulum ini untuk kamu pergunakan sendiri. (Jangan ragu untuk memberikan kami bintang juga 😊)

|

||||||

|

- **Jelajahi Scikit-learn**. Buat diri kamu familiar dengan [Scikit-learn]([https://scikit-learn.org/stable/user_guide.html), seperangkat *library* ML yang kita acu dalam pelajaran-pelajaran ini.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Apa itu Machine Learning?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Istilah 'Machine Learning' merupakan salah satu istilah yang paling populer dan paling sering digunakan saat ini. Ada kemungkinan kamu pernah mendengar istilah ini paling tidak sekali jika kamu familiar dengan teknologi. Tetapi untuk mekanisme Machine Learning sendiri, merupakan sebuah misteri bagi sebagian besar orang. Karena itu, penting untuk memahami sebenarnya apa itu Machine Learning, dan mempelajarinya langkah demi langkah melalui contoh praktis.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Google Trends memperlihatkan 'kurva tren' dari istilah 'Machine Learning' belakangan ini.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Kita hidup di sebuah alam semesta yang penuh dengan misteri yang menarik. Ilmuwan-ilmuwan besar seperti Stephen Hawking, Albert Einstein, dan banyak lagi telah mengabdikan hidup mereka untuk mencari informasi yang berarti yang mengungkap misteri dari dunia disekitar kita. Ini adalah kondisi belajar manusia: seorang anak manusia belajar hal-hal baru dan mengungkap struktur dari dunianya tahun demi tahun saat mereka tumbuh dewasa.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Otak dan indera seorang anak memahami fakta-fakta di sekitarnya dan secara bertahap mempelajari pola-pola kehidupan yang tersembunyi yang membantu anak untuk menyusun aturan-aturan logis untuk mengidentifikasi pola-pola yang dipelajari. Proses pembelajaran otak manusia ini menjadikan manusia sebagai makhluk hidup paling canggih di dunia ini. Belajar terus menerus dengan menemukan pola-pola tersembunyi dan kemudian berinovasi pada pola-pola itu memungkinkan kita untuk terus menjadikan diri kita lebih baik sepanjang hidup. Kapasitas belajar dan kemampuan berkembang ini terkait dengan konsep yang disebut dengan *[brain plasticity](https://www.simplypsychology.org/brain-plasticity.html)*. Secara sempit, kita dapat menarik beberapa kesamaan motivasi antara proses pembelajaran otak manusia dan konsep Machine Learning.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Otak manusia](https://www.livescience.com/29365-human-brain.html) menerima banyak hal dari dunia nyata, memproses informasi yang diterima, membuat keputusan rasional, dan melakukan aksi-aksi tertentu berdasarkan keadaan. Inilah yang kita sebut dengan berperilaku cerdas. Ketika kita memprogram sebuah salinan dari proses perilaku cerdas ke sebuah mesin, ini dinamakan kecerdasan buatan atau Artificial Intelligence (AI).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Meskipun istilah-stilahnya bisa membingungkan, Machine Learning (ML) adalah bagian penting dari Artificial Intelligence. **ML berkaitan dengan menggunakan algoritma-algoritma terspesialisasi untuk mengungkap informasi yang berarti dan mencari pola-pola tersembunyi dari data yang diterima untuk mendukung proses pembuatan keputusan rasional**.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Sebuah diagram yang memperlihatkan hubungan antara AI, ML, Deep Learning, dan Data Science. Infografis oleh [Jen Looper](https://twitter.com/jenlooper) terinspirasi dari [infografis ini](https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/366996/distinction-between-ai-ml-neural-networks-deep-learning-and-data-mining)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Apa yang akan kamu pelajari

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dalam kurikulum ini, kita hanya akan membahas konsep inti dari Machine Learning yang harus diketahui oleh seorang pemula. Kita membahas apa yang kami sebut sebagai 'Machine Learning klasik' utamanya menggunakan Scikit-learn, sebuah *library* luar biasa yang banyak digunakan para siswa untuk belajar dasarnya. Untuk memahami konsep Artificial Intelligence atau Deep Learning yang lebih luas, pengetahuan dasar yang kuat tentang Machine Learning sangat diperlukan, itulah yang ingin kami tawarkan di sini.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Kamu akan belajar:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Konsep inti ML

|

||||||

|

- Sejarah dari ML

|

||||||

|

- Keadilan dan ML

|

||||||

|

- Teknik regresi ML

|

||||||

|

- Teknik klasifikasi ML

|

||||||

|

- Teknik *clustering* ML

|

||||||

|

- Teknik *natural language processing* ML

|

||||||

|

- Teknik *time series forecasting* ML

|

||||||

|

- *Reinforcement learning*

|

||||||

|

- Penerapan nyata dari ML

|

||||||

|

## Yang tidak akan kita bahas

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- *deep learning*

|

||||||

|

- *neural networks*

|

||||||

|

- AI

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Untuk membuat pengalaman belajar yang lebih baik, kita akan menghindari kerumitan dari *neural network*, *deep learning* - membangun *many-layered model* menggunakan *neural network* - dan AI, yang mana akan kita bahas dalam kurikulum yang berbeda. Kami juga akan menawarkan kurikulum *data science* yang berfokus pada aspek bidang tersebut.

|

||||||

|

## Kenapa belajar Machine Learning?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Machine Learning, dari perspektif sistem, didefinisikan sebagai pembuatan sistem otomatis yang dapat mempelajari pola-pola tersembunyi dari data untuk membantu membuat keputusan cerdas.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Motivasi ini secara bebas terinspirasi dari bagaimana otak manusia mempelajari hal-hal tertentu berdasarkan data yang diterimanya dari dunia luar.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ Pikirkan sejenak mengapa sebuah bisnis ingin mencoba menggunakan strategi Machine Learning dibandingkan membuat sebuah mesin berbasis aturan yang tertanam (*hard-coded*).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Penerapan Machine Learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Penerapan Machine Learning saat ini hampir ada di mana-mana, seperti data yang mengalir di sekitar kita, yang dihasilkan oleh ponsel pintar, perangkat yang terhubung, dan sistem lainnya. Mempertimbangkan potensi besar dari algoritma Machine Learning terkini, para peneliti telah mengeksplorasi kemampuan Machine Learning untuk memecahkan masalah kehidupan nyata multi-dimensi dan multi-disiplin dengan hasil positif yang luar biasa.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Kamu bisa menggunakan Machine Learning dalam banyak hal**:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Untuk memprediksi kemungkinan penyakit berdasarkan riwayat atau laporan medis pasien.

|

||||||

|

- Untuk memanfaatkan data cuaca untuk memprediksi peristiwa cuaca.

|

||||||

|

- Untuk memahami sentimen sebuah teks.

|

||||||

|

- Untuk mendeteksi berita palsu untuk menghentikan penyebaran propaganda.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Keuangan, ekonomi, geosains, eksplorasi ruang angkasa, teknik biomedis, ilmu kognitif, dan bahkan bidang humaniora telah mengadaptasi Machine Learning untuk memecahkan masalah sulit pemrosesan data di bidang mereka.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Machine Learning mengotomatiskan proses penemuan pola dengan menemukan wawasan yang berarti dari dunia nyata atau dari data yang dihasilkan. Machine Learning terbukti sangat berharga dalam penerapannya di berbagai bidang, diantaranya adalah bidang bisnis, kesehatan, dan keuangan.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dalam waktu dekat, memahami dasar-dasar Machine Learning akan menjadi suatu keharusan bagi orang-orang dari bidang apa pun karena adopsinya yang luas.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

## 🚀 Tantangan

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Buat sketsa di atas kertas atau menggunakan aplikasi seperti [Excalidraw](https://excalidraw.com/), mengenai pemahaman kamu tentang perbedaan antara AI, ML, Deep Learning, dan Data Science. Tambahkan beberapa ide masalah yang cocok diselesaikan masing-masing teknik.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz Pasca-Pelajaran](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/2/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Ulasan & Belajar Mandiri

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Untuk mempelajari lebih lanjut tentang bagaimana kamu dapat menggunakan algoritma ML di cloud, ikuti [Jalur Belajar](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/create-no-code-predictive-models-azure-machine-learning/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa) ini.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Tugas

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Persiapan](assignment.id.md)

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Lévantate y corre

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instrucciones

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

En esta tarea no calificada, debe repasar Python y hacer que su entorno esté en funcionamiento y sea capaz de ejecutar cuadernos.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Tome esta [Ruta de aprendizaje de Python](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/python-language/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa), y luego configure sus sistemas con estos videos introductorios:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlrxD0HtieHhS8VzuMCfQD4uJ9yne1mE6

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,10 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Être opérationnel

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instructions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dans ce devoir non noté, vous devez vous familiariser avec Python et rendre votre environnement opérationnel et capable d'exécuter des notebook.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Suivez ce [parcours d'apprentissage Python](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/python-language/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa), puis configurez votre système en parcourant ces vidéos introductives :

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlrxD0HtieHhS8VzuMCfQD4uJ9yne1mE6

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Persiapan

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instruksi

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dalam tugas yang tidak dinilai ini, kamu akan mempelajari Python dan mempersiapkan *environment* kamu sehingga dapat digunakan untuk menjalankan *notebook*.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Ambil [Jalur Belajar Python](https://docs.microsoft.com/learn/paths/python-language/?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa) ini, kemudian persiapkan sistem kamu dengan menonton video-video pengantar ini:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlrxD0HtieHhS8VzuMCfQD4uJ9yne1mE6

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,116 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Sejarah Machine Learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Catatan sketsa oleh [Tomomi Imura](https://www.twitter.com/girlie_mac)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz Pra-Pelajaran](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/3/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dalam pelajaran ini, kita akan membahas tonggak utama dalam sejarah Machine Learning dan Artificial Intelligence.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sejarah Artifical Intelligence, AI, sebagai bidang terkait dengan sejarah Machine Learning, karena algoritma dan kemajuan komputasi yang mendukung ML dimasukkan ke dalam pengembangan AI. Penting untuk diingat bahwa, meski bidang-bidang ini sebagai bidang-bidang penelitian yang berbeda mulai terbentuk pada 1950-an, [algoritmik, statistik, matematik, komputasi dan penemuan teknis](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_machine_learning) penting sudah ada sebelumnya, dan saling tumpang tindih di era ini. Faktanya, orang-orang telah memikirkan pertanyaan-pertanyaan ini selama [ratusan tahun](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_artificial_intelligence): artikel ini membahas dasar-dasar intelektual historis dari gagasan 'mesin yang berpikir'.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Penemuan penting

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- 1763, 1812 [Bayes Theorem](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayes%27_theorem) dan para pendahulu. Teorema ini dan penerapannya mendasari inferensi, mendeskripsikan kemungkinan suatu peristiwa terjadi berdasarkan pengetahuan sebelumnya.

|

||||||

|

- 1805 [Least Square Theory](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Least_squares) oleh matematikawan Perancis Adrien-Marie Legendre. Teori ini yang akan kamu pelajari di unit Regresi, ini membantu dalam *data fitting*.

|

||||||

|

- 1913 [Markov Chains](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Markov_chain) dinamai dengan nama matematikawan Rusia, Andrey Markov, digunakan untuk mendeskripsikan sebuah urutan dari kejadian-kejadian yang mungkin terjadi berdasarkan kondisi sebelumnya.

|

||||||

|

- 1957 [Perceptron](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Perceptron) adalah sebuah tipe dari *linear classifier* yang ditemukan oleh psikolog Amerika, Frank Rosenblatt, yang mendasari kemajuan dalam *Deep Learning*.

|

||||||

|

- 1967 [Nearest Neighbor](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Nearest_neighbor) adalah sebuah algoritma yang pada awalnya didesain untuk memetakan rute. Dalam konteks ML, ini digunakan untuk mendeteksi berbagai pola.

|

||||||

|

- 1970 [Backpropagation](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Backpropagation) digunakan untuk melatih [feedforward neural networks](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Feedforward_neural_network).

|

||||||

|

- 1982 [Recurrent Neural Networks](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Recurrent_neural_network) adalah *artificial neural networks* yang berasal dari *feedforward neural networks* yang membuat grafik sementara.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ Lakukan sebuah riset kecil. Tanggal berapa lagi yang merupakan tanggal penting dalam sejarah ML dan AI?

|

||||||

|

## 1950: Mesin yang berpikir

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Alan Turing, merupakan orang luar biasa yang terpilih oleh [publik di tahun 2019](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Icons:_The_Greatest_Person_of_the_20th_Century) sebagai ilmuwan terhebat di abad 20, diberikan penghargaan karena membantu membuat fondasi dari sebuah konsep 'mesin yang bisa berpikir', Dia berjuang menghadapi orang-orang yang menentangnya dan keperluannya sendiri untuk bukti empiris dari konsep ini dengan membuat [Turing Test](https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-18475646), yang mana akan kamu jelajahi di pelajaran NLP kami.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 1956: Proyek Riset Musim Panas Dartmouth

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

"Proyek Riset Musim Panas Dartmouth pada *artificial intelligence* merupakan sebuah acara penemuan untuk *artificial intelligence* sebagai sebuah bidang," dan dari sinilah istilah '*artificial intelligence*' diciptakan ([sumber](https://250.dartmouth.edu/highlights/artificial-intelligence-ai-coined-dartmouth)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Setiap aspek pembelajaran atau fitur kecerdasan lainnya pada prinsipnya dapat dideskripsikan dengan sangat tepat sehingga sebuah mesin dapat dibuat untuk mensimulasikannya.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Ketua peneliti, profesor matematika John McCarthy, berharap "untuk meneruskan dasar dari dugaan bahwa setiap aspek pembelajaran atau fitur kecerdasan lainnya pada prinsipnya dapat dideskripsikan dengan sangat tepat sehingga mesin dapat dibuat untuk mensimulasikannya." Marvin Minsky, seorang tokoh terkenal di bidang ini juga termasuk sebagai peserta penelitian.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Workshop ini dipuji karena telah memprakarsai dan mendorong beberapa diskusi termasuk "munculnya metode simbolik, sistem yang berfokus pada domain terbatas (sistem pakar awal), dan sistem deduktif versus sistem induktif." ([sumber](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Dartmouth_workshop)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 1956 - 1974: "Tahun-tahun Emas"

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dari tahun 1950-an hingga pertengahan 70-an, optimisme memuncak dengan harapan bahwa AI dapat memecahkan banyak masalah. Pada tahun 1967, Marvin Minsky dengan yakin menyatakan bahwa "Dalam satu generasi ... masalah menciptakan '*artificial intelligence*' akan terpecahkan secara substansial." (Minsky, Marvin (1967), Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Penelitian *natural language processing* berkembang, pencarian disempurnakan dan dibuat lebih *powerful*, dan konsep '*micro-worlds*' diciptakan, di mana tugas-tugas sederhana diselesaikan menggunakan instruksi bahasa sederhana.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Penelitian didanai dengan baik oleh lembaga pemerintah, banyak kemajuan dibuat dalam komputasi dan algoritma, dan prototipe mesin cerdas dibangun. Beberapa mesin tersebut antara lain:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [Shakey the robot](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakey_the_robot), yang bisa bermanuver dan memutuskan bagaimana melakukan tugas-tugas secara 'cerdas'.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Shakey pada 1972

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* Eliza, sebuah 'chatterbot' awal, dapat mengobrol dengan orang-orang dan bertindak sebagai 'terapis' primitif. Kamu akan belajar lebih banyak tentang Eliza dalam pelajaran NLP.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Sebuah versi dari Eliza, sebuah *chatbot*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

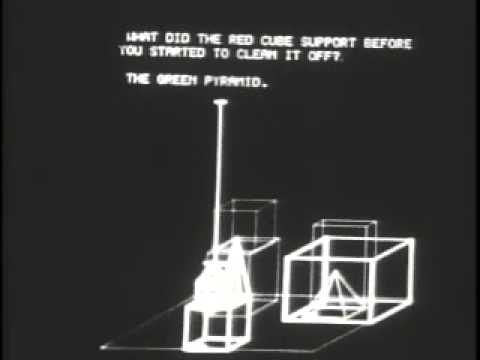

* "Blocks world" adalah contoh sebuah *micro-world* dimana balok dapat ditumpuk dan diurutkan, dan pengujian eksperimen mesin pengajaran untuk membuat keputusan dapat dilakukan. Kemajuan yang dibuat dengan *library-library* seperti [SHRDLU](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/SHRDLU) membantu mendorong kemajuan pemrosesan bahasa.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QAJz4YKUwqw "blocks world dengan SHRDLU")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> 🎥 Klik gambar diatas untuk menonton video: Blocks world with SHRDLU

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 1974 - 1980: "Musim Dingin AI"

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Pada pertengahan 1970-an, semakin jelas bahwa kompleksitas pembuatan 'mesin cerdas' telah diremehkan dan janjinya, mengingat kekuatan komputasi yang tersedia, telah dilebih-lebihkan. Pendanaan telah habis dan kepercayaan dalam bidang ini menurun. Beberapa masalah yang memengaruhi kepercayaan diri termasuk:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Keterbatasan**. Kekuatan komputasi terlalu terbatas.

|

||||||

|

- **Ledakan kombinatorial**. Jumlah parameter yang perlu dilatih bertambah secara eksponensial karena lebih banyak hal yang diminta dari komputer, tanpa evolusi paralel dari kekuatan dan kemampuan komputasi.

|

||||||

|

- **Kekurangan data**. Adanya kekurangan data yang menghalangi proses pengujian, pengembangan, dan penyempurnaan algoritma.

|

||||||

|

- **Apakah kita menanyakan pertanyaan yang tepat?**. Pertanyaan-pertanyaan yang diajukan pun mulai dipertanyakan kembali. Para peneliti mulai melontarkan kritik tentang pendekatan mereka

|

||||||

|

- Tes Turing mulai dipertanyakan, di antara ide-ide lain, dari 'teori ruang Cina' yang mengemukakan bahwa, "memprogram komputer digital mungkin membuatnya tampak memahami bahasa tetapi tidak dapat menghasilkan pemahaman yang sebenarnya." ([sumber](https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-room/))

|

||||||

|

- Tantangan etika ketika memperkenalkan kecerdasan buatan seperti si "terapis" ELIZA ke dalam masyarakat.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Pada saat yang sama, berbagai aliran pemikiran AI mulai terbentuk. Sebuah dikotomi didirikan antara praktik ["scruffy" vs. "neat AI"](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Neats_and_scruffies). Lab _Scruffy_ mengubah program selama berjam-jam sampai mendapat hasil yang diinginkan. Lab _Neat_ "berfokus pada logika dan penyelesaian masalah formal". ELIZA dan SHRDLU adalah sistem _scruffy_ yang terkenal. Pada tahun 1980-an, karena perkembangan permintaan untuk membuat sistem ML yang dapat direproduksi, pendekatan _neat_ secara bertahap menjadi yang terdepan karena hasilnya lebih dapat dijelaskan.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 1980s Sistem Pakar

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Seiring berkembangnya bidang ini, manfaatnya bagi bisnis menjadi lebih jelas, dan begitu pula dengan menjamurnya 'sistem pakar' pada tahun 1980-an. "Sistem pakar adalah salah satu bentuk perangkat lunak artificial intelligence (AI) pertama yang benar-benar sukses." ([sumber](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Expert_system)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Tipe sistem ini sebenarnya adalah _hybrid_, sebagian terdiri dari mesin aturan yang mendefinisikan kebutuhan bisnis, dan mesin inferensi yang memanfaatkan sistem aturan untuk menyimpulkan fakta baru.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Pada era ini juga terlihat adanya peningkatan perhatian pada jaringan saraf.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 1987 - 1993: AI 'Chill'

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Perkembangan perangkat keras sistem pakar terspesialisasi memiliki efek yang tidak menguntungkan karena menjadi terlalu terspesialiasasi. Munculnya komputer pribadi juga bersaing dengan sistem yang besar, terspesialisasi, dan terpusat ini. Demokratisasi komputasi telah dimulai, dan pada akhirnya membuka jalan untuk ledakan modern dari *big data*.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 1993 - 2011

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Pada zaman ini memperlihatkan era baru bagi ML dan AI untuk dapat menyelesaikan beberapa masalah yang sebelumnya disebabkan oleh kurangnya data dan daya komputasi. Jumlah data mulai meningkat dengan cepat dan tersedia secara luas, terlepas dari baik dan buruknya, terutama dengan munculnya *smartphone* sekitar tahun 2007. Daya komputasi berkembang secara eksponensial, dan algoritma juga berkembang saat itu. Bidang ini mulai mengalami kedewasaan karena hari-hari yang tidak beraturan di masa lalu mulai terbentuk menjadi disiplin yang sebenarnya.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Sekarang

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Saat ini, *machine learning* dan AI hampir ada di setiap bagian dari kehidupan kita. Era ini menuntut pemahaman yang cermat tentang risiko dan efek potensi dari berbagai algoritma yang ada pada kehidupan manusia. Seperti yang telah dinyatakan oleh Brad Smith dari Microsoft, "Teknologi informasi mengangkat isu-isu yang menjadi inti dari perlindungan hak asasi manusia yang mendasar seperti privasi dan kebebasan berekspresi. Masalah-masalah ini meningkatkan tanggung jawab bagi perusahaan teknologi yang menciptakan produk-produk ini. Dalam pandangan kami, mereka juga menyerukan peraturan pemerintah yang bijaksana dan untuk pengembangan norma-norma seputar penggunaan yang wajar" ([sumber](https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/12/18/102365/the-future-of-ais-impact-on-society/)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Kita masih belum tahu apa yang akan terjadi di masa depan, tetapi penting untuk memahami sistem komputer dan perangkat lunak serta algoritma yang dijalankannya. Kami berharap kurikulum ini akan membantu kamu untuk mendapatkan pemahaman yang lebih baik sehingga kamu dapat memutuskan sendiri.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTtDfKgLm54 "Sejarah Deep Learning")

|

||||||

|

> 🎥 Klik gambar diatas untuk menonton video: Yann LeCun mendiskusikan sejarah dari Deep Learning dalam pelajaran ini

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

## 🚀Tantangan

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Gali salah satu momen bersejarah ini dan pelajari lebih lanjut tentang orang-orang di baliknya. Ada karakter yang menarik, dan tidak ada penemuan ilmiah yang pernah dibuat dalam kekosongan budaya. Apa yang kamu temukan?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz Pasca-Pelajaran](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/4/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Ulasan & Belajar Mandiri

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Berikut adalah item untuk ditonton dan didengarkan:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Podcast dimana Amy Boyd mendiskusikan evolusi dari AI](http://runasradio.com/Shows/Show/739)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EJt3_bFYKss "Sejarah AI oleh Amy Boyd")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Tugas

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Membuat sebuah *timeline*](assignment.id.md)

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Créer une frise chronologique

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instructions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Utiliser [ce repo](https://github.com/Digital-Humanities-Toolkit/timeline-builder), créer une frise chronologique de certains aspects de l'histoire des algorithmes, des mathématiques, des statistiques, de l'IA ou du machine learning, ou une combinaison de ceux-ci. Vous pouvez vous concentrer sur une personne, une idée ou une longue période d'innovations. Assurez-vous d'ajouter des éléments multimédias.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Rubrique

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

| Critères | Exemplaire | Adéquate | A améliorer |

|

||||||

|

| -------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------- | ------------------------------------ | ------------------------------------------------------------------ |

|

||||||

|

| | Une chronologie déployée est présentée sous forme de page GitHub | Le code est incomplet et non déployé | La chronologie est incomplète, pas bien recherchée et pas déployée |

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Membuat sebuah *timeline*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instruksi

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Menggunakan [repo ini](https://github.com/Digital-Humanities-Toolkit/timeline-builder), buatlah sebuah *timeline* dari beberapa aspek sejarah algoritma, matematika, statistik, AI, atau ML, atau kombinasi dari semuanya. Kamu dapat fokus pada satu orang, satu ide, atau rentang waktu pemikiran yang panjang. Pastikan untuk menambahkan elemen multimedia.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Rubrik

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

| Kriteria | Sangat Bagus | Cukup | Perlu Peningkatan |

|

||||||

|

| -------- | ------------------------------------------------- | --------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------- |

|

||||||

|

| | *Timeline* yang dideploy disajikan sebagai halaman GitHub | Kode belum lengkap dan belum dideploy | *Timeline* belum lengkap, belum diriset dengan baik dan belum dideploy |

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 年表を作成する

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 指示

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[このリポジトリ](https://github.com/Digital-Humanities-Toolkit/timeline-builder) を使って、アルゴリズム・数学・統計学・人工知能・機械学習、またはこれらの組み合わせに対して、歴史のひとつの側面に関する年表を作成してください。焦点を当てるのは、ひとりの人物・ひとつのアイディア・長期間にわたる思想のいずれのものでも構いません。マルチメディアの要素を必ず加えるようにしてください。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 評価基準

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

| 基準 | 模範的 | 十分 | 要改善 |

|

||||||

|

| ---- | -------------------------------------- | ------------------------------------ | ------------------------------------------------------------ |

|

||||||

|

| | GitHub page に年表がデプロイされている | コードが未完成でデプロイされていない | 年表が未完成で、十分に調査されておらず、デプロイされていない |

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 建立一个时间轴

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 说明

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

使用这个 [仓库](https://github.com/Digital-Humanities-Toolkit/timeline-builder),创建一个关于算法、数学、统计学、人工智能、机器学习的某个方面或者可以综合多个以上学科来讲。你可以着重介绍某个人,某个想法,或者一个经久不衰的思想。请确保添加了多媒体元素在你的时间线中。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 评判标准

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

| 标准 | 优秀 | 中规中矩 | 仍需努力 |

|

||||||

|

| ------------ | ---------------------------------- | ---------------------- | ------------------------------------------ |

|

||||||

|

| | 有一个用 GitHub page 展示的 timeline | 代码还不完整并且没有部署 | 时间线不完整,没有经过充分的研究,并且没有部署 |

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Explore Fairlearn

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instrucciones

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

En esta lección, aprendió sobre Fairlearn, un "proyecto open-source impulsado por la comunidad para ayudar a los científicos de datos a mejorar la equidad de los sistemas de AI." Para esta tarea, explore uno de los [cuadernos](https://fairlearn.org/v0.6.2/auto_examples/index.html) de Fairlearn e informe sus hallazgos en un documento o presentación.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Rúbrica

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

| Criterios | Ejemplar | Adecuado | Necesita mejorar |

|

||||||

|

| -------- | --------- | -------- | ----------------- |

|

||||||

|

| | Un documento o presentación powerpoint es presentado discutiendo los sistemas de Fairlearn, el cuadernos que fue ejecutado, y las conclusiones extraídas al ejecutarlo | Un documento es presentado sin conclusiones | No se presenta ningún documento |

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Jelajahi Fairlearn

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Instruksi

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dalam pelajaran ini kamu telah belajar mengenai Fairlearn, sebuah "proyek *open-source* berbasis komunitas untuk membantu para *data scientist* meningkatkan keadilan dari sistem AI." Untuk penugasan kali ini, jelajahi salah satu dari [notebook](https://fairlearn.org/v0.6.2/auto_examples/index.html) yang disediakan Fairlearn dan laporkan penemuanmu dalam sebuah paper atau presentasi.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Rubrik

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

| Kriteria | Sangat Bagus | Cukup | Perlu Peningkatan |

|

||||||

|

| -------- | --------- | -------- | ----------------- |

|

||||||

|

| | Sebuah *paper* atau presentasi powerpoint yang membahas sistem Fairlearn, *notebook* yang dijalankan, dan kesimpulan yang diambil dari hasil menjalankannya | Sebuah paper yang dipresentasikan tanpa kesimpulan | Tidak ada paper yang dipresentasikan |

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,107 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Técnicas de Machine Learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

El proceso de creación, uso y mantenimiento de modelos de machine learning, y los datos que se utilizan, es un proceso muy diferente de muchos otros flujos de trabajo de desarrollo. En esta lección, demistificaremos el proceso, y describiremos las principales técnicas que necesita saber. Vas a:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Comprender los procesos que sustentan el machine learning a un alto nivel.

|

||||||

|

- Explorar conceptos básicos como 'modelos', 'predicciones', y 'datos de entrenamiento'

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Cuestionario previo a la conferencia](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/7/)

|

||||||

|

## Introducción

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A un alto nivel, el arte de crear procesos de machine learning (ML) se compone de una serie de pasos:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. **Decidir sobre la pregunta**. La mayoría de los procesos de ML, comienzan por hacer una pregunta que no puede ser respondida por un simple programa condicional o un motor basado en reglas. Esas preguntas a menudo giran en torno a predicciones basadas en una recopilación de datos.

|

||||||

|

2. **Recopile y prepare datos**. Para poder responder a su pregunta, necesita datos. La calidad y, a veces, cantidad de sus datos determinarán que tan bien puede responder a su pregunta inicial. La visualización de datos es un aspecto importante de esta fase. Esta fase también incluye dividir los datos en un grupo de entrenamiento y pruebas para construir un modelo.

|

||||||

|

3. **Elige un método de entrenamiento**. Dependiendo de su pregunta y la naturaleza de sus datos, debe elegir cómo desea entrenar un modelo para reflejar mejor sus datos y hacer predicciones precisas contra ellos. Esta es la parte de su proceso de ML que requiere experiencia específica y, a menudo, una cantidad considerable de experimetación.

|

||||||

|

4. **Entrena el model**. Usando sus datos de entrenamiento, usará varios algoritmos para entrenar un modelo para reconocer patrones en los datos. El modelo puede aprovechar las ponderaciones internas que se pueden ajustar para privilegiar ciertas partes de los datos sobre otras para construir un modelo mejor.

|

||||||

|

5. **Evaluar el modelo**. Utiliza datos nunca antes vistos (sus datos de prueba) de su conjunto recopilado para ver cómo se está desempeñando el modelo.

|

||||||

|

6. **Ajuste de parámetros**. Según el rendimiento de su modelo, puede rehacer el proceso utilizando diferentes parámetros, o variables, que controlan el comportamiento de los algoritmos utlizados para entrenarl el modelo.

|

||||||

|

7. **Predecir**. Utilice nuevas entradas para probar la precisión de su modelo.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Que pregunta hacer

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Las computadoras son particularmente hábiles para descubrir patrones ocultos en los datos. Esta utlidad es muy útil para los investigadores que tienen preguntas sobre un dominio determinado que no pueden responderse fácilmente mediante la creación de un motor de reglas basado en condicionales. Dada una tarea actuarial, por ejemplo, un científico de datos podría construir reglas artesanales sobre la mortalidad de los fumadores frente a los no fumadores.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sin embargo, cuandos se incorporan muchas otras variables a la ecuación, un modelo de ML podría resultar más eficiente para predecir las tasas de mortalidad futuras en funciòn de los antecedentes de salud. Un ejemplo más alegre podría hacer predicciones meteorólogicas para el mes de abril en una ubicación determinada que incluya latitud, longitud, cambio climático, proximidad al océano, patrones de la corriente en chorro, y más.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ Esta [presentación de diapositivas](https://www2.cisl.ucar.edu/sites/default/files/0900%20June%2024%20Haupt_0.pdf) sobre modelos meteorológicos ofrece una perspectiva histórica del uso de ML en el análisis meteorológico.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Tarea previas a la construcción

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Antes de comenzar a construir su modelo, hay varias tareas que debe comletar. Para probar su pregunta y formar una hipótesis basada en las predicciones de su modelo, debe identificar y configurar varios elementos.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Datos

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Para poder responder su pregunta con cualquier tipo de certeza, necesita una buena cantidad de datos del tipo correcto.

|

||||||

|

Hay dos cosas que debe hacer en este punto:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Recolectar datos**. Teniendo en cuenta la lección anterior sobre la equidad en el análisis de datos, recopile sus datos con cuidado. Tenga en cuenta la fuente de estos datos, cualquier sesgo inherente que pueda tener y documente su origen.

|

||||||

|

- **Preparar datos**. Hay varios pasos en el proceso de preparación de datos. Podría necesitar recopilar datos y normalizarlos si provienen de diversas fuentes. Puede mejorar la calidad y cantidad de los datos mediante varios métodos, como convertir strings en números (como hacemos en [Clustering](../../5-Clustering/1-Visualize/README.md)). También puede generar nuevos datos, basados en los originales (como hacemos en [Clasificación](../../4-Classification/1-Introduction/README.md)). Puede limpiar y editar los datos (como lo haremos antes de la lección [Web App](../../3-Web-App/README.md)). Por último, es posible que también deba aleotizarlo y mezclarlo, según sus técnicas de entrenamiento.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ Despúes de recopilar y procesar sus datos, tómese un momento para ver si su forma le permitirá responder a su pregunta. ¡Puede ser que los datos no funcionen bien en su tarea dada, como descubriremos en nuestras lecciones de[Clustering](../../5-Clustering/1-Visualize/README.md)!

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Seleccionando su variable característica

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Una [característica](https://www.datasciencecentral.com/profiles/blogs/an-introduction-to-variable-and-feature-selection) es una propiedad medible de sus datos. En muchos conjuntos de datos, se expresa como un encabezado de columna como 'fecha', 'tamaño' o 'color'. Su variable característica, generalmente representada como `y` en el código, representa la respuesta a la pregunta que está tratando de hacer a sus datos: en diciembre, ¿qué calabazas de **color** serán las más baratas?, en San Francisco, ¿que vecinadarios tendrán el mejor **precio** de bienes raíces?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

🎓 **Selección y extracción de características** ¿ Cómo sabe que variable elegir al construir un modelo? Probablemente pasará por un proceso de selección o extracción de características para elegir las variables correctas para mayor un mayor rendimiento del modelo. Sin embargo, no son lo mismo: "La extracción de características crea nuevas características a partir de funciones de las características originales, mientras que la selección de características devuelve un subconjunto de las características." ([fuente](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Feature_selection))

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Visualiza tus datos

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Un aspecto importante del conjunto de herramientas del científico de datos es el poder de visualizar datos utilizando varias bibliotecas excelentes como Seaborn o MatPlotLib. Representar sus datos visualmente puede permitirle descubrir correlaciones ocultas que puede aprovechar. Sus visualizaciones también pueden ayudarlo a descubrir sesgos o datos desequilibrados. (como descubrimos en [Clasificación](../../4-Classification/2-Classifiers-1/README.md)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Divide tu conjunto de datos

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Antes del entrenamiento, debe dividir su conjunto de datos en dos o más partes de tamaño desigual que aún represente bien los datos.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Entrenamiento**. Esta parte del conjunto de datos se ajusta a su modelo para entrenarlo. Este conjunto constituye la mayor parte del conjunto de datos original.

|

||||||

|

- **Pruebas**. Un conjunto de datos de pruebas es un grupo independiente de datos, a menudo recopilado a partir de los datos originales, que se utiliza para confirmar el rendimiento del modelo construido.

|

||||||

|

- **Validación**. Un conjunto de validación es un pequeño grupo independiente de ejemplos que se usa para ajustar los hiperparámetros o la arquitectura del modelo para mejorar el modelo. Dependiendo del tamaño de de su conjunto de datos y de la pregunta que se está haciendo, es posible que no necesite crear este tercer conjunto (como notamos en [Pronóstico se series de tiempo](../../7-TimeSeries/1-Introduction/README.md)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Contruye un modelo

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Usando sus datos de entrenamiento, su objetivo es construir un modelo, o una representación estadística de sus datos, usando varios algoritmos para **entrenarlo**. El entrenamiento de un modelo lo expone a los datos y le permite hacer suposiciones sobre los patrones percibidos que descubre, valida y rechaza.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Decide un método de entrenamiento

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dependiendo de su pregunta y la naturaleza de sus datos, elegirá un método para entrenarlos. Pasando por la [documentación de Scikit-learn ](https://scikit-learn.org/stable/user_guide.html) - que usamos en este curso - puede explorar muchas formas de entrenar un modelo. Dependiendo de su experiencia, es posible que deba probar varios métodos diferentes para construir el mejor modelo. Es probable que pase por un proceso en el que los científicos de datos evalúan el rendimiento de un modelo alimentándolo con datos no vistos anteriormente por el modelo, verificando la precisión, el sesgo, y otros problemas que degradan la calidad, y seleccionando el método de entrenamieto más apropiado para la tarea en custión.

|

||||||

|

### Entrena un modelo

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Armado con sus datos de entrenamiento, está listo para 'fit'(ajustarlos/entrenarlos) para crear un modelo. Notará que en muchas bibliotecas de ML, encontrará el código 'model.fit' - es en este momento cuando envías sus datos como una matriz de valores (generalmente 'X') y una variable característica (generalmente 'Y').

|

||||||

|

### Evaluar el modelo

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Una vez que se completa el proceso de entrenamiento (puede tomar muchas iteraciones, o 'épocas', entrenar un modelo de gran tamaño), podrá evaluar la calidad del modelo utilizando datos de prueba para medir su rendimiento. Estos datos son un subconjunto de los datos originales que el modelo no ha analizado previamente. Puede imprimir una tabla de métricas sobre la calidad de su modelo.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

🎓 **Ajuste del modelo (Model fitting)**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

En el contexto del machine learning, el ajuste del modelo se refiere a la precisión de la función subyacente del modelo cuando intenta analizar datos con los que no está familiarizado.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

🎓 **Ajuste insuficiente (Underfitting)** y **sobreajuste (overfitting)** son problemas comunes que degradan la calidad del modelo, ya que el modelo no encaja suficientemente bien, o encaja demasiado bien. Esto hace que el modelo haga predicciones demasiado estrechamente alineadas o demasiado poco alineadas con sus datos de entrenamiento. Un modelo sobreajustadoo (overfitting) predice demasiado bien los datos de entrenamiento porque ha aprendido demasiado bien los detalles de los datos y el ruido. Un modelo insuficentemente ajustado (Underfitting) es es preciso, ya que ni puede analizar con precisión sus datos de entrenamiento ni los datos que aún no ha 'visto'.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Infografía de [Jen Looper](https://twitter.com/jenlooper)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Ajuste de parámetros

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Una vez que haya completado su entrenamiento inicial, observe la calidad del modelo y considere mejorarlo ajustando sus 'hiperparámetros'. Lea más sobre el proceso [en la documentación](https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/machine-learning/how-to-tune-hyperparameters?WT.mc_id=academic-15963-cxa).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Predicción

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Este es el momento en el que puede usar datos completamente nuevos para probar la precisión de su modelo. En una configuración de ML aplicada, donde está creando activos web para usar el modelo en producción, este proceo puede implicar la recopilación de la entrada del usuario (presionar un botón, por ejemplo) para establecer una variable y enviarla al modelo para la inferencia, o evaluación.

|

||||||

|

En estas lecciones, descubrirá cómo utilizar estos pasos para preparar, construir, probar, evaluar, y predecir - todos los gestos de un científico de datos y más, a medida que avanza en su viaje para convertirse en un ingeniero de machine learning 'full stack'.

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 🚀Desafío

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dibuje un diagrama de flujos que refleje los pasos de practicante de ML. ¿Dónde te ves ahora mismo en el proceso? ¿Dónde predice que encontrará dificultades? ¿Qué te parece fácil?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Cuestionario previo a la conferencia](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/8/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Revisión & Autoestudio

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Busque en línea entrevistas con científicos de datos que analicen su trabajo diario. Aquí está [uno](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3IjgbbCEfs).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Asignación

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Entrevistar a un científico de datos](assignment.md)

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,105 @@

|

|||||||

|

# Teknik-teknik Machine Learning

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Proses membangun, menggunakan, dan memelihara model machine learning dan data yang digunakan adalah proses yang sangat berbeda dari banyak alur kerja pengembangan lainnya. Dalam pelajaran ini, kita akan mengungkap prosesnya dan menguraikan teknik utama yang perlu Kamu ketahui. Kamu akan:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Memahami gambaran dari proses yang mendasari machine learning.

|

||||||

|

- Menjelajahi konsep dasar seperti '*models*', '*predictions*', dan '*training data*'.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## [Quiz Pra-Pelajaran](https://jolly-sea-0a877260f.azurestaticapps.net/quiz/7/)

|

||||||

|

## Pengantar

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Gambaran membuat proses machine learning (ML) terdiri dari sejumlah langkah:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. **Menentukan pertanyaan**. Sebagian besar proses ML dimulai dengan mengajukan pertanyaan yang tidak dapat dijawab oleh program kondisional sederhana atau mesin berbasis aturan (*rules-based engine*). Pertanyaan-pertanyaan ini sering berkisar seputar prediksi berdasarkan kumpulan data.

|

||||||

|

2. **Mengumpulkan dan menyiapkan data**. Untuk dapat menjawab pertanyaanmu, Kamu memerlukan data. Bagaimana kualitas dan terkadang kuantitas data kamu akan menentukan seberapa baik kamu dapat menjawab pertanyaan awal kamu. Memvisualisasikan data merupakan aspek penting dari fase ini. Fase ini juga mencakup pemisahan data menjadi kelompok *training* dan *testing* untuk membangun model.

|

||||||

|

3. **Memilih metode training**. Tergantung dari pertanyaan dan sifat datamu, Kamu perlu memilih bagaimana kamu ingin men-training sebuah model untuk mencerminkan data kamu dengan baik dan membuat prediksi yang akurat terhadapnya. Ini adalah bagian dari proses ML yang membutuhkan keahlian khusus dan seringkali perlu banyak eksperimen.

|

||||||

|

4. **Melatih model**. Dengan menggunakan data *training*, kamu akan menggunakan berbagai algoritma untuk melatih model guna mengenali pola dalam data. Modelnya mungkin bisa memanfaatkan *internal weight* yang dapat disesuaikan untuk memberi hak istimewa pada bagian tertentu dari data dibandingkan bagian lainnya untuk membangun model yang lebih baik.

|

||||||

|

5. **Mengevaluasi model**. Gunakan data yang belum pernah dilihat sebelumnya (data *testing*) untuk melihat bagaimana kinerja model.

|

||||||

|

6. **Parameter tuning**. Berdasarkan kinerja modelmu, Kamu dapat mengulang prosesnya menggunakan parameter atau variabel yang berbeda, yang mengontrol perilaku algoritma yang digunakan untuk melatih model.

|

||||||

|

7. **Prediksi**. Gunakan input baru untuk menguji keakuratan model kamu.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Pertanyaan apa yang harus ditanyakan?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Komputer sangat ahli dalam menemukan pola tersembunyi dalam data. Hal ini sangat membantu peneliti yang memiliki pertanyaan tentang domain tertentu yang tidak dapat dijawab dengan mudah dari hanya membuat mesin berbasis aturan kondisional (*conditionally-based rules engine*). Untuk tugas aktuaria misalnya, seorang data scientist mungkin dapat membuat aturan secara manual seputar mortalitas perokok vs non-perokok.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Namun, ketika banyak variabel lain dimasukkan ke dalam persamaan, model ML mungkin terbukti lebih efisien untuk memprediksi tingkat mortalitas di masa depan berdasarkan riwayat kesehatan masa lalu. Contoh yang lebih menyenangkan mungkin membuat prediksi cuaca untuk bulan April di lokasi tertentu berdasarkan data yang mencakup garis lintang, garis bujur, perubahan iklim, kedekatan dengan laut, pola aliran udara (Jet Stream), dan banyak lagi.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ [Slide deck](https://www2.cisl.ucar.edu/sites/default/files/0900%20June%2024%20Haupt_0.pdf) ini menawarkan perspektif historis pada model cuaca dengan menggunakan ML dalam analisis cuaca.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Tugas Pra-Pembuatan

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sebelum mulai membangun model kamu, ada beberapa tugas yang harus kamu selesaikan. Untuk menguji pertanyaan kamu dan membentuk hipotesis berdasarkan prediksi model, Kamu perlu mengidentifikasi dan mengonfigurasi beberapa elemen.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Data

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Untuk dapat menjawab pertanyaan kamu dengan kepastian, Kamu memerlukan sejumlah besar data dengan jenis yang tepat. Ada dua hal yang perlu kamu lakukan pada saat ini:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Mengumpulkan data**. Ingat pelajaran sebelumnya tentang keadilan dalam analisis data, kumpulkan data kamu dengan hati-hati. Waspadai sumber datanya, bias bawaan apa pun yang mungkin dimiliki, dan dokumentasikan asalnya.

|

||||||

|

- **Menyiapkan data**. Ada beberapa langkah dalam proses persiapan data. Kamu mungkin perlu menyusun data dan melakukan normalisasi jika berasal dari berbagai sumber. Kamu dapat meningkatkan kualitas dan kuantitas data melalui berbagai metode seperti mengonversi string menjadi angka (seperti yang kita lakukan di [Clustering](../../5-Clustering/1-Visualize/translations/README.id.md)). Kamu mungkin juga bisa membuat data baru berdasarkan data yang asli (seperti yang kita lakukan di [Classification](../../4-Classification/1-Introduction/translations/README.id.md)). Kamu bisa membersihkan dan mengubah data (seperti yang kita lakukan sebelum pelajaran [Web App](../3-Web-App/translations/README.id.md)). Terakhir, Kamu mungkin juga perlu mengacaknya dan mengubah urutannya, tergantung pada teknik *training* kamu.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

✅ Setelah mengumpulkan dan memproses data kamu, luangkan waktu sejenak untuk melihat apakah bentuknya memungkinkan kamu untuk menjawab pertanyaan yang kamu maksudkan. Mungkin data tidak akan berkinerja baik dalam tugas yang kamu berikan, seperti yang kita temukan dalam pelajaran [Clustering](../../5-Clustering/1-Visualize/translations/README.id.md).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Memilih variabel fiturmu

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sebuah [fitur](https://www.datasciencecentral.com/profiles/blogs/an-introduction-to-variable-and-feature-selection) adalah sebuah properti yang dapat diukur dalam data kamu. Dalam banyak dataset, properti dinyatakan sebagai sebuah heading kolom seperti 'date' 'size' atau 'color'. Variabel fitur kamu yang biasanya direpresentasikan sebagai `y` dalam kode, mewakili jawaban atas pertanyaan yang kamu coba tanyakan tentang data kamu: pada bulan Desember, labu dengan **warna** apa yang akan paling murah? di San Francisco, lingkungan mana yang menawarkan **harga** real estate terbaik?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

🎓 **Feature Selection dan Feature Extraction** Bagaimana kamu tahu variabel mana yang harus dipilih saat membangun model? Kamu mungkin akan melalui proses pemilihan fitur (*Feature Selection*) atau ekstraksi fitur (*Feature Extraction*) untuk memilih variabel yang tepat untuk membuat model yang berkinerja paling baik. Namun, keduanya tidak sama: "Ekstraksi fitur membuat fitur baru dari fungsi fitur asli, sedangkan pemilihan fitur mengembalikan subset fitur." ([sumber](https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Feature_selection))

|

||||||

|

### Visualisasikan datamu

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Aspek penting dari toolkit data scientist adalah kemampuan untuk memvisualisasikan data menggunakan beberapa *library* seperti Seaborn atau MatPlotLib. Merepresentasikan data kamu secara visual memungkinkan kamu mengungkap korelasi tersembunyi yang dapat kamu manfaatkan. Visualisasimu mungkin juga membantu kamu mengungkap data yang bias atau tidak seimbang (seperti yang kita temukan dalam [Classification](../../4-Classification/2-Classifiers-1/translations/README.id.md)).

|

||||||

|

### Membagi dataset

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sebelum memulai *training*, Kamu perlu membagi dataset menjadi dua atau lebih bagian dengan ukuran yang tidak sama tapi masih mewakili data dengan baik.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Training**. Bagian dataset ini digunakan untuk men-training model kamu. Bagian dataset ini merupakan mayoritas dari dataset asli.

|

||||||

|

- **Testing**. Sebuah dataset tes adalah kelompok data independen, seringkali dikumpulkan dari data yang asli yang akan digunakan untuk mengkonfirmasi kinerja dari model yang dibuat.

|

||||||

|

- **Validating**. Dataset validasi adalah kumpulan contoh mandiri yang lebih kecil yang kamu gunakan untuk menyetel hyperparameter atau arsitektur model untuk meningkatkan model. Tergantung dari ukuran data dan pertanyaan yang kamu ajukan, Kamu mungkin tidak perlu membuat dataset ketiga ini (seperti yang kita catat dalam [Time Series Forecasting](../7-TimeSeries/1-Introduction/translations/README.id.md)).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Membuat sebuah model

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dengan menggunakan data *training*, tujuan kamu adalah membuat model atau representasi statistik data kamu menggunakan berbagai algoritma untuk **melatihnya**. Melatih model berarti mengeksposnya dengan data dan mengizinkannya membuat asumsi tentang pola yang ditemukan, divalidasi, dan diterima atau ditolak.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Tentukan metode training

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Tergantung dari pertanyaan dan sifat datamu, Kamu akan memilih metode untuk melatihnya. Buka dokumentasi [Scikit-learn](https://scikit-learn.org/stable/user_guide.html) yang kita gunakan dalam pelajaran ini, kamu bisa menjelajahi banyak cara untuk melatih sebuah model. Tergantung dari pengalamanmu, kamu mungkin perlu mencoba beberapa metode yang berbeda untuk membuat model yang terbaik. Kemungkinan kamu akan melalui proses di mana data scientist mengevaluasi kinerja model dengan memasukkan data yang belum pernah dilihat, memeriksa akurasi, bias, dan masalah penurunan kualitas lainnya, dan memilih metode training yang paling tepat untuk tugas yang ada.

|

||||||

|

### Melatih sebuah model

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Berbekal data *training*, Kamu siap untuk menggunakannya untuk membuat model. Kamu akan melihat di banyak *library* ML mengenai kode 'model.fit' - pada saat inilah kamu mengirimkan data kamu sebagai *array* nilai (biasanya 'X') dan variabel fitur (biasanya 'y' ).

|

||||||

|

### Mengevaluasi model

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Setelah proses *training* selesai (ini mungkin membutuhkan banyak iterasi, atau 'epoch', untuk melatih model besar), Kamu akan dapat mengevaluasi kualitas model dengan menggunakan data tes untuk mengukur kinerjanya. Data ini merupakan subset dari data asli yang modelnya belum pernah dianalisis sebelumnya. Kamu dapat mencetak tabel metrik tentang kualitas model kamu.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

🎓 **Model fitting**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Dalam konteks machine learning, *model fitting* mengacu pada keakuratan dari fungsi yang mendasari model saat mencoba menganalisis data yang tidak familiar.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

🎓 **Underfitting** dan **overfitting** adalah masalah umum yang menurunkan kualitas model, karena model tidak cukup akurat atau terlalu akurat. Hal ini menyebabkan model membuat prediksi yang terlalu selaras atau tidak cukup selaras dengan data trainingnya. Model overfit memprediksi data *training* terlalu baik karena telah mempelajari detail dan noise data dengan terlalu baik. Model underfit tidak akurat karena tidak dapat menganalisis data *training* atau data yang belum pernah dilihat sebelumnya secara akurat.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||